the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

In-depth characterization of diazotroph activity across the western tropical South Pacific hotspot of N2 fixation (OUTPACE cruise)

Sophie Bonnet

Mathieu Caffin

Hugo Berthelot

Olivier Grosso

Mar Benavides

Sandra Helias-Nunige

Cécile Guieu

Marcus Stenegren

Rachel Ann Foster

Here we report N2 fixation rates from a ∼ 4000 km transect in the western and central tropical South Pacific, a particularly undersampled region in the world ocean. Water samples were collected in the euphotic layer along a west to east transect from 160∘ E to 160∘ W that covered contrasting trophic regimes, from oligotrophy in the Melanesian archipelago (MA) waters to ultra-oligotrophy in the South Pacific Gyre (GY) waters. N2 fixation was detected at all 17 sampled stations with an average depth-integrated rate of 631 ± 286 (range 196–1153 ) in MA waters and of 85 ± 79 (range 18–172 ) in GY waters. Two cyanobacteria, the larger colonial filamentous Trichodesmium and the smaller UCYN-B, dominated the enumerated diazotroph community (> 80 %) and gene expression of the nifH gene (cDNA > 105 nifH copies L−1) in MA waters. Single-cell isotopic analyses performed by nanoscale secondary ion mass spectrometry (nanoSIMS) at selected stations revealed that Trichodesmium was always the major contributor to N2 fixation in MA waters, accounting for 47.1–83.8 % of bulk N2 fixation. The most plausible environmental factors explaining such exceptionally high rates of N2 fixation in MA waters are discussed in detail, emphasizing the role of macro- and micro-nutrient (e.g., iron) availability, seawater temperature and currents.

In the ocean, nitrogen (N) availability in surface waters controls primary production and the export of organic matter (Dugdale and Goering, 1967; Eppley and Peterson, 1979; Moore et al., 2013). The major external source of new N to the surface ocean is biological di-nitrogen (N2) fixation (100–150 Tg N yr−1, Gruber, 2008), the reduction of atmospheric gas (N2) dissolved in seawater into ammonia (). The process of N2 fixation is mediated by diazotrophic organisms that possess the nitrogenase enzyme, which is encoded by a suite of nif genes. These organisms provide new N to the surface ocean and act as natural fertilizers, contributing to sustaining ocean productivity and eventually carbon (C) sequestration through the N2-primed prokaryotic C pump (Caffin et al., 2018a; Karl et al., 2003, 2012). This N source is continuously counteracted by N losses, mainly driven by denitrification and anammox, which convert reduced forms of N (nitrate, , nitrite , ) into N2. Despite the critical importance of the N inventory in regulating primary production and export, the spatial distribution of N gains and losses in the ocean is still poorly resolved.

A global-scale modeling study predicted that the highest rates of N2 fixation would be located in the South Pacific Ocean (Deutsch et al., 2007; Gruber, 2016). These authors also concluded that processes leading to N gains and losses are spatially coupled to oxygen-deficient zones such as in the eastern tropical South Pacific (ETSP), which harbors -poor but phosphate-rich surface waters, i.e., potentially ideal niches for N2 fixation (Zehr and Turner, 2001). However, recent field studies based on several cruises and independent approaches, including 15N2 incubation-based measurements and geochemical δ15N budgets, have consistently measured low N2 fixation rates (average range ∼ 0–60 ) in the surface ETSP waters (Dekaezemacker et al., 2013; Fernández et al., 2011, 2015; Knapp et al., 2016; Loescher et al., 2014). Low activity in the ETSP has been largely attributed to iron (Fe) limitation (Bonnet et al., 2017; Dekaezemacker et al., 2013), as Fe is a major component of the nitrogenase enzyme complex required for N2 fixation (Raven, 1988). However, the western tropical South Pacific (WTSP) was recently identified as having high N2 fixation activity (Bonnet et al., 2017), and collectively these studies plead for a basin-wide spatial decoupling between N2 fixation and denitrification in the South Pacific Ocean.

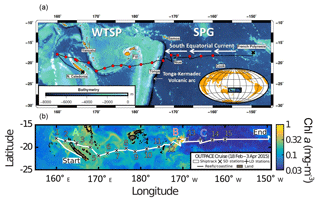

Figure 1(a) Map of the western and central Pacific and associated seas (courtesy T. Wagener and A. De Verneil). (b) Sampling locations superimposed on composite sea surface Chl a concentrations during the OUTPACE cruise (19 February–3 April, quasi-Lagrangian weighted mean Chl a). Short-duration (X) and long-duration (+) stations are indicated. The satellite data are weighted in time by each pixel's distance from the ship's average daily position for the entire cruise. The white line shows the vessel route (data from the hull-mounted ADCP positioning system; courtesy A. De Verneil).

The WTSP is a vast oceanic region extending from Australia in the west to the western boundary of the South Pacific Gyre in the east (hereafter referred to as GY waters) (Fig. 1). It has been chronically undersampled (Luo et al., 2012) as compared to the tropical North Atlantic (Benavides and Voss, 2015) and North Pacific (e.g., Böttjer et al., 2017) oceans; however, recent oceanographic surveys performed in the western part of the WTSP, in the Solomon, Bismarck (Berthelot et al., 2017; Bonnet et al., 2009, 2015) and Arafura (Messer et al., 2015; Montoya et al., 2004) seas, report extremely high N2 fixation rates (> 600 , i.e., an order of magnitude higher than in the ETSP) throughout the year. In these regions, high N2 fixation has been attributed to sea surface temperatures > 25 ∘C and continuous nutrient inputs of terrigenous and volcanic origin (Labatut et al., 2014; Radic et al., 2011). The central and eastern parts of the WTSP, a vast oceanic region bordering Melanesian archipelagoes (New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Fiji) up to the Tonga trench (hereafter referred to as MA waters) have been far less investigated. One study (Shiozaki et al., 2014) reported high surface N2 fixation rates close to the Melanesian islands in relation to nutrients supplied by land runoff. However, the lack of direct N2 fixation measurements over the full photic layer impedes accurate N budget estimates in this region. In addition, the reasons for such an ecological success of diazotrophs in the WTSP are still under debate (Bonnet et al., 2017) as the horizontal and vertical distribution of environmental parameters potentially controlling N2 fixation, in particular measured Fe concentrations, are still scarce in this region.

Recurrent blooms of the filamentous cyanobacterium Trichodesmium, one of the most abundant diazotrophs in our oceans (Luo et al., 2012), have been consistently reported in the WTSP since the James Cook (Cook, 1842) and Charles Darwin expeditions, and later confirmed by satellite observations (Dupouy et al., 2011, 2000) and microscopic enumerations (Shiozaki et al., 2014; Tenório et al., 2018). However, molecular studies based on the nifH gene abundances have shown high densities of unicellular diazotrophic cyanobacteria (UCYN) in the WTSP (Moisander et al., 2010). Three main groups of UCYN (A, B and C) can be distinguished based on nifH gene sequences. In the warm (> 25 ∘C) waters of the Solomon Sea, UCYN from group B (UCYN-B) co-occur with Trichodesmium at the surface, and together dominate the diazotrophic community (Bonnet et al., 2015), while UCYN-C are also occasionally abundant (Berthelot et al., 2017). Further south in the Coral and Tasman seas, UCYN-A dominates the diazotroph community (Bonnet et al., 2015; Moisander et al., 2010). Both studies reported a transition zone from UCYN-B-dominated communities in warm (> 25 ∘C) surface waters to UCYN-A-dominated communities in colder (< 25 ∘C) waters of the western part of the WTSP. Further east in the MA waters, Trichodesmium and UCYN-B co-occur and account for the majority of total nifH genes detected (Stenegren et al., 2018). Although molecular methods greatly enhanced our understanding of the biogeographical distribution of diazotrophs in the WTSP, DNA-based nifH counts do not equate to metabolic activity. Thus, the contribution of each dominant group to bulk N2 fixation is still lacking in the WTSP. Previous studies showed that different diazotrophs have different fates in the ocean: some are directly exported, and others release and transfer part of the recently fixed N to the planktonic food web and indirectly fuel export of organic matter (Bonnet et al., 2016a, b; Karl et al., 2012). Consequently assessing the relative contribution of each dominating group of diazotrophs to overall N2 fixation is critical to assess the biogeochemical impact of N2 fixation in the WTSP.

In the present study, we report new bulk and group-specific N2 fixation rate measurements from a ∼ 4000 km transect in the western and central tropical South Pacific. The goals of the study were (i) to quantify both horizontal and vertical distribution of N2 fixation rates in the photic layer in relation to environmental parameters, (ii) to quantify the relative contribution of the dominant diazotrophs (Trichodesmium and UCYN-B) to N2 fixation based on cell-specific measurements, and (iii) to assess the potential biogeochemical impact of N2 fixation in this region.

Samples were collected during the 45-day OUTPACE (Oliotrophic to UlTra oligotrophic PACific Experiment) cruise (DOI: https://doi.org/10.17600/15000900) onboard the R/V L'Atalante in February–March 2015 (austral summer). The west to east zonal transect along ∼ 19∘ S started in Noumea (New Caledonia) and ended in Papeete (French Polynesia) (Fig. 1). It covered a trophic gradient from oligotrophy (deep chlorophyll maximum (DCM) located at ∼ 100 m) in MA waters around New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Fiji and Tonga, to ultra-oligotrophy (DCM located at 115–150 m) in GY waters located at the western boundary of the South Pacific Gyre (Moutin et al., 2017, for details on this cruise). Data were collected at 17 stations including 14 short-duration (SD; 8 h) stations (SD1 to SD15; note that SD13 was not sampled) and 3 long-duration (LD; 7 days) stations (LDA, LDB and LDC). Vertical (0–200 m) profiles of temperature, salinity, and chlorophyll fluorescence were obtained at all 17 stations using a Seabird 911 plus CTD (conductivity, temperature, depth) equipped with a Wetlabs ECO-AFL/FL fluorometer. Seawater samples were collected by 12 L Niskin bottles mounted on the CTD rosette.

2.1 Macro-nutrient and dissolved Fe concentration analyses

Samples for the quantification of nitrate () and dissolved inorganic phosphorus (DIP) concentrations were collected at 12 depths between 0 and 200 m in acid-washed polyethylene bottles, poisoned with mercuric chloride (HgCl2, final concentration 20 mg L−1) and stored at 4 ∘C until analysis. Concentrations were determined using standard colorimetric techniques (Aminot and Kérouel, 2007) on a Bran Luebbe AA3 autoanalyzer. Detection limits for the procedures were 0.05 µmol L−1 for and DIP.

Samples for determining dissolved Fe concentrations were collected and analyzed as described in Guieu et al. (2018). Briefly, samples were collected using a Titane rosette mounted with 24 Teflon-coated 12 L GoFlos deployed with a Kevlar cable. Dissolved Fe concentrations were measured by flow injection with online preconcentration and chemiluminescence detection according to Bonnet and Guieu (2006). The reliability of the method was monitored by analyzing the D1 SAFe seawater standard (Johnson et al., 2007), and an internal acidified seawater standard was measured daily to monitor the stability of the analysis.

The sampling and analytical methods used to analyze the other parameters reported in the correlation table (Table 2) are described in detail in the methods sections for related papers in this issue (Bock et al., 2018; Fumenia et al., 2018; Stenegren et al., 2018; Van Wambeke et al., 2018).

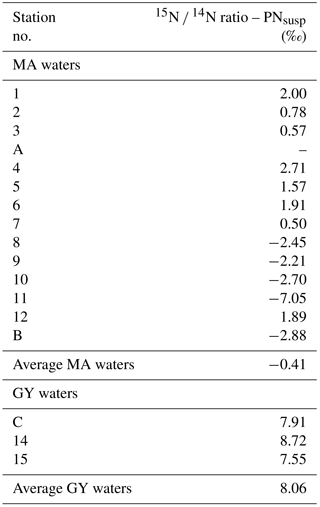

Table 115N ∕ 14N ratio of suspended particulate nitrogen (PN) (average over the photic layer) across the OUTPACE transect.

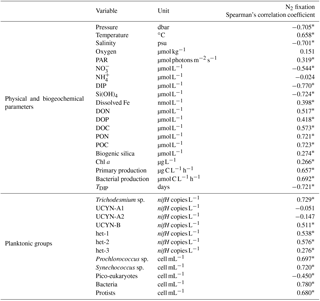

Table 2Summary of relationships between measured N2 fixation rates and various physical and biogeochemical parameters. Also shown are correlations between measured rates and the several diazotrophic or non-diazotrophic planktonic groups enumerated at the respective stations. The corresponding unit is given for each parameter, and Spearman's rank correlation (n=102, α=0.05) is provided; significant correlations (p < 0.05) are indicated by an asterisk (∗).

2.2 Bulk N2 fixation rate measurements

Whole water (bulk) N2 fixation rates were measured in triplicate at all 17 stations using the 15N2 isotopic tracer technique (adapted from Montoya et al., 1996). The 15N2 bubble technique was intentionally chosen due to the time limitation on making enriched 15N2 seawater inoculates (e.g., 6–9 depths = 6–9 inoculates) and the larger sample bottles required for making proper estimates of activity in oligotrophic environments. In addition, we aimed to avoid any potential overestimation due to trace metal and dissolved organic matter (DOM) contaminations often associated with the preparation of the 15N2-enriched seawater (Klawonn et al., 2015; Wilson et al., 2012) in our incubation bottles as Fe and DOM have been found to control N2 fixation or nifH gene expression in this region (Benavides et al., 2017; Moisander et al., 2011). However, the 15N ∕ 14N ratio of the N2 pool available for N2 fixation (the term AN2 used in Montoya et al., 1996) was measured in all incubation bottles by membrane inlet mass spectrometry (MIMS) to ensure accurate rate calculations (see below).

Seawater samples were collected from Niskin bottles into 10 % HCl-washed, sample-rinsed (three times) light-transparent polycarbonate (2.3 L) bottles from six depths (75, 50, 20, 10, 1, and 0.1 % surface irradiance levels) at all short-duration stations SD1 to SD15 and nine depths (75, 50, 35, 20, 10, 3, 1, 0.3, and 0.1 % surface irradiance levels) at LD A, LDB and LD C, corresponding to the sub-surface (5 m) down to 80 to 180 m, depending on the station. Bottles were sealed with caps fitted with silicon septa and amended with 2 mL of 98.9 at. % 15N2 (Cambridge isotopes). The purity of the 15N2 Cambridge isotope stocks was previously checked by Dabundo et al. (2014) and more recently by Benavides et al. (2015) and Bonnet et al. (2016a). They were found to be lower than mol : mol of 15N2, leading to a potential N2 fixation rate overestimation of < 1 %. Each bottle was shaken 20 times to break the 15N2 bubble and facilitate its dissolution, and was incubated for 24 h. At SD stations, bottles were incubated in on-deck incubators connected to surface circulating seawater at the specified irradiances using blue screening as the duration of the station (8 h) was too short to deploy in situ mooring lines. At LD stations (7 days), one profile was incubated following the same methodology in on-deck incubators and another replicate profile was incubated in situ for comparison on a drifting mooring line located at the same depth from which the samples were collected. Incubations were stopped by filtering the entire incubation bottle onto pre-combusted (450 ∘C, 4 h) 25 mm diameter glass fiber filters (GF/F, Whatman, 0.7 µm nominal pore size). Filters were subsequently dried at 60 ∘C for 24 h before analysis of 15N ∕ 14N ratios and particulate N (PN) determinations using an elemental analyzer coupled to a mass spectrometer (EA-IRMS, Integra CN, SerCon Ltd) as described in Bonnet et al. (2011).

To ensure accurate rate calculations, the 15N ∕ 14N ratio of the N2 pool in the incubation bottles was measured on each profile from triplicate surface incubation bottles from SD1 to SD14 and at all depths at SD15 and LD stations. Briefly, 12 mL was subsampled after incubation into Exetainers fixed with HgCl2 (final concentration 20 mg L−1) that were preserved upside down in the dark at 4 ∘C until analyzed using a MIMS according to Kana et al. (1994). Lastly, we collected time zero samples at each station to determine the natural N isotopic signature of ambient particulate N (PN). The minimum quantifiable rates (quantification limit, QL) calculated using standard propagation of errors via the observed variability between replicate samples measured according to Gradoville et al. (2017) were 0.035 nmol N L−1 d−1.

Discrete N2 fixation rate measurements were depth integrated over the photic layer using trapezoidal integration procedures. Briefly, the N2 fixation at each pair of depths is averaged, and then multiplied by the difference between the two depths to get a total N2 fixation in that depth interval. These depth interval values are then summed over the entire depth range to get the integrated N2 fixation rate. The rate nearest the surface is assumed to be constant up to 0 m (Knap et al., 1996).

2.3 Statistical analyses

Spearman's rank correlation was used to examine the potential relationships between N2 fixation rates and hydrological, biogeochemical, and biological parameters across the longitudinal transect (n=102, α=0.05). A non-parametric Mann–Whitney test (α=0.05) was used to compare the MIMS data obtained following on-deck versus in situ incubations, and to compare nutrient and Chl a distributions between the western part and the eastern part of the transect.

2.4 Group-specific N2 fixation rate measurements

2.4.1 Experimental procedures

At three stations along the transect (SD2, SD6, LDB), where Trichodesmium and UCYN-B accounted for > 90 % of the total diazotrophic community (see below and Stenegren et al., 2018), eight additional polycarbonate (2.3 L) bottles were collected from the surface (50 % light irradiance) to determine Trichodesmium and UCYN-B-specific N2 fixation rates by nanoSIMS and quantify their contribution to bulk N2 fixation. Two of these bottles were amended with 15N2 as described above for further nanoSIMS analyses on individual cells (the six remaining bottles were used for DNA and RNA analyses; see below) and were incubated for 24 h with the incubation bottles dedicated to bulk N2 fixation measurements in on-deck incubators as described above. To recover large-size diazotrophs (Trichodesmium) after incubation, 1.5 L was filtered on 10 µm pore size 25 mm diameter polycarbonate filters. The cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde (PFA) (2 % final concentration) for 1 h at ambient temperature (∼ 25 ∘C) and the filters were then stored at −20 ∘C until nanoSIMS analyses. To recover small-size diazotrophs (UCYN-B), samples were collected for further cell sorting by flow cytometry prior to nanoSIMS; 1 L of the remaining 15N2 labelled bottle was filtered onto 0.2 µm pore size 47 mm polycarbonate filters. Filters were quickly placed in a 5 mL cryotube filled with 0.2 µm filtered seawater with PFA (2 % final concentration) for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. The cryovials were vortexed for 10 s to detach the cells from the filter (Thompson et al., 2012) and stored at −80 ∘C until cell sorting. Cell sorting of UCYN-B was performed on a Becton Dickinson Influx Mariner (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) high-speed cell sorter of the Regional Flow Cytometry Platform for Microbiology (PRECYM), hosted by the Mediterranean Institute of Oceanography, as described in Bonnet et al. (2016a) and Berthelot et al. (2016). After sorting, the cells were dropped onto a 0.2 µm pore size polycarbonate 13 mm diameter polycarbonate filter connected to a low-pressure vacuum pump, and then stored at −80 ∘C until nanoSIMS analyses. Special care was taken to drop the cells on a surface as small as possible (∼ 5 mm in diameter) to ensure the highest cell density possible to facilitate subsequent nanoSIMS analyses.

2.4.2 Abundance of diazotrophs by microscopy and qPCR methods

The abundance of Trichodesmium filaments and the average number of cells per filament were determined microscopically: 1 to 2.2 L was filtered on 2 µm polycarbonate filters. The cells were fixed with PFA prepared with filtered seawater (2 % final concentration) for 1 h at 4 ∘C and stored at −20 ∘C until counting using an epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axioplan, Jena, Germany) fitted with a green (510–560 nm) excitation filter. The whole filter was counted and the number of cells per trichome were counted on at least 10 filaments per station.

Four other diazotrophic phylotypes were quantified using quantitative PCR (qPCR) as they were not easily quantifiable by standard epifluorescence microscopy: UCYN-A1, UCYN-B and two heterocystous symbionts of diatom–diazotroph associations (DDAs): Richelia intracellularis associated with Rhizosolenia spp. (het-1) and R. intracellularis associated with Hemiaulus spp. (het-2). Triplicate 2.3 L bottles were filtered onto 25 mm diameter 0.2 µm Supor filters with a 0.2 µm pore size at each station using a peristaltic pump. The DNA extraction and TaqMAN qPCR assays are fully described in Stenegren et al. (2018). To quantify nifH gene expression, additional triplicate 2.3 L bottles were filtered as described above. The filters were placed into pre-sterilized bead-beater tubes (Biospec Products Inc., Bartlesville, OK, USA) containing a 250 µL Lysis buffer (Qiagen RNeasy) amended with 1 % β-mercaptoethanol and 30 µL of 0.1 mm glass beads (Biospec Products Inc.). The time of filtering for RNA varied between stations (17:00–21:00). Filters were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 ∘C until RNA extraction. The RNA extraction and reverse transcription (RT) were performed as previously described using a Super-Script III first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA) including the appropriate negative controls (water and No-RT) (Foster et al., 2010). The nifH gene expression for het-1, het-2, Trichodesmium, UCYN-A1, and UCYN-B was as described previously (Foster et al., 2010).

2.4.3 nanoSIMS analyses, data processing and group-specific rate calculations

NanoSIMS analyses were performed using an N50 nanoSIMS instrument (Cameca, Gennevilliers, France) at the French National Ion MicroProbe Facility according to Bonnet et al. (2016a, b) and Berthelot et al. (2016). Briefly, a ∼ 1.3 pA cesium (16 KeV) primary beam focused onto a ∼ 100 nm spot diameter was scanned across a 256×256 or 512×512 pixel raster (depending on the image size) with a counting time of 1 ms per pixel. Samples were pre-sputtered prior to analyses with a current of ∼ 10 pA for at least 2 min to achieve sputtering equilibrium and ensure a consistent implantation and analysis of the cell interior by removing the cell surface. Negative secondary ions (12C14N−, 12C15N−) were collected by electron multiplier detectors, and secondary electrons were also imaged simultaneously. A total of 10–50 serial quantitative secondary ion images were generated that were combined to create the final image. Mass resolving power was ∼ 8000 in order to resolve isobaric interferences; 20 to 100 planes were generated for each cell analyzed. NanoSIMS runs are time-intensive and not designed for routine analysis, but a minimum of 250 cells of UCYN-B per station and 30 Trichodesmium filament portions were analyzed to take into account the variability of activity among the population.

Data were processed using the LIMAGE software. Briefly, all scans were corrected for any drift of the beam and sample stage during acquisition. Isotope ratio images were created by adding the secondary ion counts for each recorded secondary ion for each pixel over all recorded planes and dividing the total counts by the total counts of a selected reference mass. Individual Trichodesmium filaments and UCYN-B cells were easily identified on nanoSIMS images that were used to define regions of interest (ROIs). For each ROI, the 15N ∕ 14N ratio was calculated.

Trichodesmium and UCYN-B cellular biovolume was calculated from cell-diameter measurements performed on ∼ 50 cells or trichomes per station using an epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axioplan, Jena, Germany) fitted with a green (510–560 nm) excitation filter. UCYN-B had a spherical shape and Trichodesmium cells were assumed to have a cylindrical shape. The carbon content per cell was estimated from the biovolume according to Verity et al. (1992) and the N content was calculated based on C : N ratios of 6 for Trichodesmium (Carpenter et al., 2004) and 5 for UCYN-B (Dekaezemacker and Bonnet, 2011; Knapp et al., 2012). 15N assimilation rates were expressed “per cell” and calculated as follows (Foster et al., 2011, 2013): assimilation (mol N cell−1 d−1) = (15Nex × Ncon)∕ Nsr, where 15Nex is the excess 15N enrichment of the individual cells measured by nanoSIMS after 24 h of incubation relative to the time zero value, Ncon is the N content of each cell determined as described above, and Nsr is the excess 15N enrichment of the source pool (N2) in the experimental bottles determined by MIMS (see above). Standard deviations were calculated using the variability of N isotopic signatures measured by nanoSIMS on replicate cells. The relative contribution of Trichodesmium and UCYN-B to bulk N2 fixation was calculated by multiplying cell-specific N assimilation by the cell abundance of each group, relative to bulk N2 fixation determined at the same time.

3.1 Environmental conditions

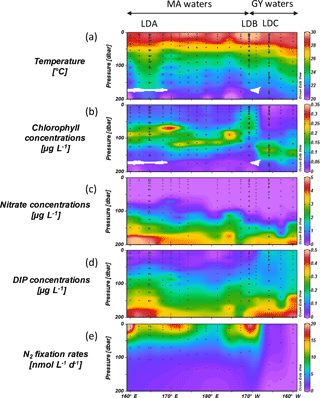

Seawater temperature ranged from 21.4 to 30.0 ∘C in the sampled photic layer (0 to ∼ 80–180 m) over the cruise transect (Fig. 2a). The mixed layer depth (MLD) calculated according to the de Boyer Montégut et al. (2004) method was located around 20–40 m throughout the zonal transect: maximum temperatures were measured in the surface mixed layer (∼ 0–20∕40 m) and remained almost constant along the longitudinal transect with 29.1 ± 0.3 ∘C in MA waters and 29.5 ± 0.4 ∘C in GY waters.

Figure 2Horizontal and vertical distributions of (a) seawater temperature (∘C), (b) chlorophyll fluorescence (µg L−1), (c) (µmol L−1), (d) DIP (µmol L−1) and (e) N2 fixation rates (nmol N L−1 d−1) across the OUTPACE transect. LD stations are noted and the extent of the two defined sub-regions: MA: Melanesian archipelago waters, GY: South Pacific Gyre waters. Y axis: pressure (dbar), X axis: longitude; black dots correspond to sampling depths at the various SD and LD stations.

Based on other hydrographic measurements (dissolved nutrients, dissolved Fe and Chl a concentrations), the longitudinal transect was divided into two sub-regions: (1) the MA region from station SD1 (160∘ E) to LDB (165∘ W), and (2) the GY sub-region from station LDB (165 ∘ W) to SD15 (160∘ W). Chl a concentration in the upper 50 m was significantly (p< 0.05) higher in MA waters (0.17 µg L−1 on average) than in GY waters (0.06 µg L−1 on average) (Figs. 1 and 2b). The DCM was located around 80–100 m in MA waters and deepened to ∼ 150 m in GY waters, indicating higher oligotrophy in the GY region. Surface concentrations (Fig. 2c) were consistently close to or below the detection limit (0.05 µmol L−1) in the upper water column (0–50 m) throughout the transect and the depth of the nitracline gradually deepened from ∼ 75–100 m in MA waters to ∼ 115 m in GY waters. DIP concentrations were slightly higher than or close to detection limits (0.05 µmol L−1) in MA surface waters (0–50 m), and the phosphacline was shallower (20–45 m) than the nitracline and DIP concentrations increased significantly (p < 0.05) in GY waters and ranged from 0.13 to 0.17 µmol L−1 (Fig. 2d).

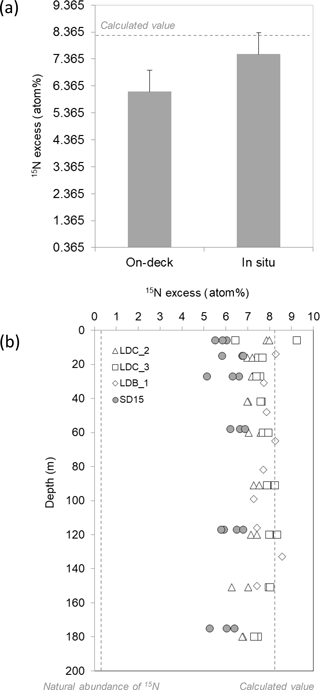

3.2 N isotopic signature of the N2 pool after incubation

The 15N enrichment of the N2 pool after 24 h of incubation with the 15N2 tracer was on average 6.145 ± 0.798 at. % (n=54) in bottles incubated in on-deck incubators and significantly higher (p < 0.05) in bottles incubated on the mooring line (7.548 ± 0.557 at. % (n=44), Fig. 3a). However, the depth of incubation on the mooring line (between 5 and 180 m) did not have any significant effect (p > 0.05) on the isotopic signature of the N2 pool at LDB and LDC, which remained constant over the water column (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3(a) The average measured 15N ∕ 14N ratio of the N2 pool in the incubation bottles incubated either in on-deck incubators (n=54) or in situ (mooring line) (n=44). The dashed lines represent the theoretical value (∼ 8.2 at. %) calculated assuming complete isotopic equilibration between the gas bubble and the seawater based on gas constants. Error bars represent the standard deviation (b) depth profiles of the 15N ∕ 14N ratio of the N2 pool in the incubation bottles incubated either in on-deck incubators (filled symbols) or on an in situ mooring line (open symbols).

3.3 Natural isotopic signature of suspended particles and N2 fixation rates

The natural N isotopic signature of suspended particles measured over the photic layer was on average −0.41 ‰ in MA waters and 8.06 ‰ in GY waters (Table 1). Those isotopic values were used as time zero samples to calculate N2 fixation rates.

N2 fixation was detected at all 17 sampled stations and the average measured N2 fixation rates in the two previously defined sub-regions were (1) 8.9 ± 10 nmol N L−1 d−1 (range QL-48 nmol N L−1 d−1) over the photic layer in MA waters, and 2) 0.5 ± 0.6 nmol N L−1 d−1 (range QL-4.0 nmol N L−1 d−1) in GY waters (Fig. 2e). In MA waters, N2 fixation was largely restricted to the mixed layer, where average rates were 15 nmol N L−1 d−1, with local maxima (> 20 nmol N L−1 d−1) at stations SD1, SD6 and LDB and local minima (< 5 nmol N L−1 d−1) at SD8 and SD10. In GY waters, maximum rates reached 1–2 nmol N L−1 d−1 and were located deeper in the water column (∼ 50 m). When integrated over the photic layer, N2 fixation represented an average net N addition of 631 ± 286 (range 196–1153 ) in MA waters and of 85 ± 79 (range 18–172 ) in GY waters.

N2 fixation rates were significantly positively correlated with seawater temperature and photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) (p < 0.05), significantly negatively correlated with depth and salinity (p < 0.05) and not significantly correlated with dissolved oxygen concentrations (p > 0.05) (Table 2). N2 fixation rates were significantly positively correlated with dissolved Fe, dissolved organic N (DON), phosphorus (DOP), carbon (DOC), particulate organic N (PON), particulate organic carbon (POC), biogenic silica (BSi), Chl a concentrations, and primary and bacterial production (p < 0.05), and significantly negatively correlated with concentration of dissolved nutrients: , NH, DIP and silicate (p < 0.05). N2 fixation rates were significantly positively correlated with nifH abundances for Trichodesmium spp., UCYN-B and the symbionts of DDAs (het-1, het-2) (p < 0.05) and not significantly correlated with UCYN-A1 and UCYN-A2 abundances (p > 0.05) (Table 2). Regarding non-diazotrophic plankton, N2 fixation rates were significantly positively correlated with Prochlorococcus spp., Synechococcus spp., heterotrophic bacteria and protist abundances (p < 0.05) and significantly negatively correlated with picoeukaryotes (p < 0.05).

3.4 Contribution of Trichodesmium and UCYN-B to N2 fixation and nitrogenase gene expression

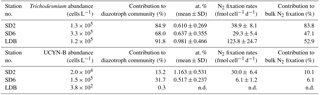

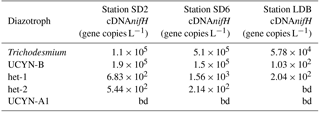

At the three stations where cell-specific N2 fixation rates were estimated by nanoSIMS (SD2, SD6 and LDB), the most abundant diazotroph phylotype was Trichodesmium with 1.3 × 105, 3.3 × 105 and 1.2 × 105 cells L−1, respectively, followed by UCYN-B, whose abundances were 2.0 × 104, 1.5 × 105 and 3.8 × 102 nifH copies L−1, respectively. Het-1 and het-2 combined were 1 to 2 orders of magnitude lower, ranging from 1.0 to 9.9 × 103 nifH copies L−1, and UCYN-A1 were below detection at the three stations. In summary, Trichodesmium and UCYN-B accounted for 98.2, 99.8 and 92.1 % of the total diazotroph community (based on the phylotypes targeted here) at SD2, SD6 and LDB, respectively (Table 3).

The 15N ∕ 14N ratios of individual cells/trichomes of UCYN-B and Trichodesmium were measured via nanoSIMS analyses and used to estimate single-cell N2 fixation rates. A summary of the enrichment values and cell-specific N2 fixation is provided in Table 3. Individual trichomes exhibited significant 15N enrichments (0.610 ± 0.269, 0.637 ± 0.355 and 0.981 ± 0.466 at. % at stations SD2, SD6 and LDB, respectively) compared with time zero samples (0.369 ± 0.002 at. %). UCYN-B were also significantly 15N-enriched, with 1.163 ± 0.531 and 0.517 ± 0.237 at. % at SD2 and SD6, respectively (note that no UCYN-B could be sorted and analyzed by nanoSIMS at LDB as they accounted for only 0.3 % of the diazotroph community). Cell-specific N2 fixation rates of Trichodesmium were 38.9 ± 8.1, 29.3 ± 5.4 and 123.8 ± 24.8 fmol N cell−1 d−1 at SD2, SD6 and LDB. Cell-specific N2 fixation of UCYN-B was 30.0 ± 6.4 and 6.1 ± 1.2 fmol N cell−1 d−1 at SD1 and SD6. The contribution of Trichodesmium to bulk N2 fixation was 83.8, 47.1 and 52.9 % at stations SD2, SD6 and LDB, respectively. The contribution of UCYN-B was 10.1 and 6.1 % at SD2 and SD6, respectively (Table 3).

The in situ nifH expression for all diazotroph groups targeted by qPCR was estimated using a TaqMAN quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) (Table 4). The sampling and filtering time (17:00–21:00 h) was not optimal for quantifying the nifH gene expression for all diazotrophs; however, it provides useful information about which diazotrophs were potentially active during the experiment and complements the nanoSIMS analysis which measures the in situ activity. Both Trichodesmium and UCYN-B dominated the biomass (Stenegren et al., 2018), as did their nifH gene expression at all three stations, especially SD2 and SD6. Of the two DDAs, het-1 had a higher nifH gene expression, which was consistent with its higher nifH abundance by DNA qPCR (Stenegren et al., 2018). UCYN-A1 was consistently below detection for the nifH gene expression and was also the least detected diazotroph by nifH qPCR (Stenegren et al., 2018).

4.1 Methodological considerations: the importance of measuring the 15N ∕ 14N ratio of the N2 pool

Our understanding of the marine N cycle relies on accurate estimates of N fluxes to and from the ocean. Here we decided to use the “bubble addition method” to minimize potential trace metal and organic matter contaminations, which may have resulted in overestimating rates (Klawonn et al., 2015). Moreover, a recent extensive meta-analysis (13 studies, 368 observations) between bubble and enriched amendment experiments to measure 15N2 rates reported that underestimation of N2 fixation is negligible in experiments that last 12–24 h (e.g., error is −0.2 %); hence our 24 h based experiments should be within a small amount of error (Wannicke et al., 2018). However, we paid careful attention to accurately measure the term AN2 to avoid any potential underestimation and reveal that the way bottles are incubated (on-deck versus in situ) has a great influence on the AN2 value, and thus on N2 fixation rates.

Our MIMS results measured a significantly (p < 0.05) lower 15N enrichment of the N2 pool (6.145 ± 0.798 at. %) when bottles were incubated in on-deck incubators compared to when bottles were incubated on the mooring line (7.548 ± 0.557 at. %). This suggests that the 15N2 dissolution is much more efficient when bottles are incubated in situ, probably due to the higher pressure in seawater at the depth of incubation (1.5 to 19 bars between 5 and 180 m) compared to the pressure in the on-deck incubators (1 bar). The seawater temperature checked regularly in the on-deck incubators was equivalent to ambient surface temperature and likely did not explain the differences observed. This result highlights the need to perform routine MIMS measurements to use the most accurate AN2 value for rate calculations, independently of the 15N2 approach used (gas or dissolved). In our study, the theoretical AN2 value based on gas constant calculations (Weiss, 1970) was ∼ 8.2 at. %, so the deviation from this value is more important when bottles are incubated in on-deck incubators as compared to when they are incubated in situ. This suggests that the use of the bubble addition method without MIMS measurement potentially leads to higher underestimations when bottles are incubated in on-deck incubators, which is the case in the great majority of marine N2 fixation studies published so far (Luo et al., 2012). We are aware that the dissolution kinetics of 15N2 in the incubation bottles may have been progressive along the 24 h of incubation (Mohr et al., 2010); therefore, the N2 fixation rates provided here represent conservative values.

Despite the AN2 value being different according to the incubation mode, it did not change with the depth of incubation on the mooring line, indicating that a slightly higher pressure than atmospheric pressure (1.5 bar at 5 m depth) is enough to promote the 15N2 dissolution. It also indicates that the slightly lower seawater temperature (22–24 ∘C) recorded at ∼ 100–180 m where the deepest samples were incubated likely did not affect the solubilization of the 15N2 gas. In our study, the vertical profiles performed at LD stations and incubated either on-deck in triplicate or in situ in triplicate reveal identical (p > 0.05) N2 fixation rates regardless of the incubation method used (Caffin et al., 2018b). This indicates that in situ incubations and on-deck incubations that simulate appropriate light levels are a valid methodology for 15N2 fixation rate measurements on cruises during which mooring lines cannot be deployed, as long as routine measurements of the isotopic ratio of the N2 pool are performed in incubation bottles.

4.2 Drivers of high N2 fixation rates in the WTSP?

N2 fixation rates measured in MA waters (average 631 ± 286 ) are 3 to 4 times higher than model predictions for this area (150–200 , Gruber, 2016). They are in the upper range of the higher category (100–1000 ) of rates defined by Luo et al. (2012) in the N2 fixation MAREDAT database for the global ocean and thus identify the WTSP as an area for high N2 fixation in the global ocean. Recent studies performed in the western part of the WTSP, i.e., in the Solomon, Bismarck (Berthelot et al., 2017; Bonnet et al., 2009, 2015) and Arafura (Messer et al., 2015; Montoya et al., 2004) seas, also reveal extremely high rates (> 600 ), indicating that this high N2 fixation activity area extends geographically west–east from Australia to Tonga and north–south from the Equator to 25–30∘ S, covering a vast ocean area of ∼ 13×106 km2 (i.e., ∼ 20 % of the South Pacific Ocean area). However, the driver(s) for diazotrophy in this region is(are) still poorly resolved and raise(s) the question of which factors influence the distribution and activity of N2 fixation in the ocean. In a global-scale study conducted by Luo et al. (2014), which investigated the correlations between N2 fixation and a variety of environmental parameters commonly accepted to control this process, they concluded that SST (or surface solar radiation) was the best predictor to explain the spatial distribution of N2 fixation in the surface ocean. Below we highlight the most plausible factors explaining such high N2 fixation rates in our study area.

Seawater temperature. Seawater temperature was unlikely to be the factor explaining the differences in N2 fixation rates observed between MA and GY waters, as it was consistently high (> 28 ∘C in the surface mixed layer) and optimal for the growth and nitrogenase activity of most diazotrophs (Breitbarth et al., 2007; Nübel et al., 1997) all along the cruise transect. This indicates that other factors such as nutrient availability may explain the distribution of N2 fixation.

DIP availability. The ∼ 4000 km transect was divided into two main sub-regions: (1) the MA waters, harboring typical oligotrophic conditions with surface and DIP concentrations close to detection limits (0.05 µmol L−1), a nitracline located at 75–100 m, moderate surface Chl a concentrations (∼ 0.17 µg L−1), a DCM located at ∼ 80–100 m and very high N2 fixation rates (631 ± 286 on average), and (2) the GY waters harboring ultra-oligotrophic conditions with undetectable , a deeper nitracline (115 m), and comparatively high DIP concentrations (0.15 µmol L−1), very low Chl a concentrations (0.06 µg L−1, DCM ∼ 150 m) and low N2 fixation rates (85 ± 79 ).

In the -depleted MA waters, low DIP concentrations are indicative of the consumption of DIP by the planktonic community, including diazotrophs. This is consistent with the negative correlation found between N2 fixation and DIP turnover time (the ratio between DIP concentrations and DIP uptake rates) (Table 2) and suggests a higher DIP limitation when N2 fixation is high and consumes DIP. The high DIP concentrations (> 0.1 µmol L−1) in GY surface waters compared to MA waters are consistent with former studies that consider the South Pacific Gyre as a high phosphate, low chlorophyll ecosystem (Moutin et al., 2008), in which DIP accumulates in the absence of and low N2 fixation activity. In the high phosphate, low chlorophyll scenario, the community is limited by temperature and/or Fe availability (Moutin et al., 2008; Bonnet et al., 2008). During the OUTPACE cruise, the DIP turnover time was variable but close to or below 2 days in MA waters (Moutin et al., 2018), indicating a potential limitation by DIP at some stations. Trichodesmium, the most abundant and major contributor to N2 fixation during the cruise, is known to synthesize hydrolytic enzymes in order to acquire P from the dissolved organic phosphorus pool (DOP) (Sohm and Capone, 2006). Moreover, Trichodesmium spp. differs from the other major diazotroph UCYN-B enumerated on the cruise in the forms of organic P it can synthesize. It is thus likely that DOP species that favored Trichodesmium over UCYN-B played a role in maintaining high Trichodesmium biomass in MA waters. It has to be noted that average DIP turnover times in MA waters were always much higher than those typically measured in severely DIP-limited environments such as the Mediterranean and Sargasso seas (e.g., Moutin et al., 2008), suggesting that DIP concentrations are generally favorable for the development of certain diazotrophs in the WTSP, and do not alone explain why N2 fixation is high in MA waters and low in GY waters. However, it is likely that the depletion of DIP stocks at the end of the austral summer season forces the decline of diazotrophic blooms in the WTSP (Moutin et al., 2005), concomitantly with the decline of SST.

Fe availability. Before OUTPACE, our knowledge on Fe sources and concentrations in the WTSP was limited, especially in MA waters. During OUTPACE, Guieu et al. (2018) reported high dissolved Fe concentrations in MA waters (range 0.2–66.2 nmol L−1, 1.7 nmol L−1 on average over the photic layer), i.e., significantly (p < 0.05) higher than those reported in GY waters (range 0.2–0.6 nmol L−1, 0.3 nM on average over the photic layer). The low dissolved Fe concentrations measured in the GY waters agree well with previous reports for the same region (Blain et al., 2008; Fitzsimmons et al., 2014). However, the high dissolved Fe concentrations measured in MA waters were previously undocumented and reveal several maxima (> 50 nmol L−1) between stations SD7 and SD11, indicative of intense fertilization processes taking place in this region. Guieu et al. (2018) found that atmospheric deposition measured during the cruise in this region was too low to explain the observed dissolved Fe concentrations in the surface water column. The seafloor of the WTSP hosts the Tonga–Kermadec subduction zone which stretches 2500 km from New Zealand to the Tonga archipelago (Fig. 1). It has among the highest densities of submarine volcanoes associated with hydrothermal vents recorded in the ocean (2.6 vents / 100 km, Massoth et al., 2007), which discharge large quantities of material into the water column, including biogeochemically relevant elements such as Fe and Mn. Guieu et al. (2018) used hydrological data recorded by Argo float in situ measurements, atlas data and simulations from a general ocean circulation model to argue that the high dissolved Fe concentrations may be sustained by a submarine source. They show that such Fe inputs could spread throughout the WTSP through mesoscale activity mainly westward through the South Equatorial Current, SEC (Fig. 1). Guieu et al. (2018) hypothesize that the high dissolved Fe concentrations in MA waters compared to the GY ones is due to shallow inputs of hydrothermal origin together with potential Fe input from islands themselves (Shiozaki et al., 2014). In our study, dissolved Fe concentrations were significantly positively correlated with N2 fixation and help to explain the distribution of N2 fixation rates measured across the OUTPACE transect.

In summary, our hypothesis to explain the spatial distribution of N2 fixation in MA waters is the following: when high DIP waters flow westward from the ETSP through the SEC and cross the South Pacific Gyre, N2-fixing organisms do not develop despite optimal SST (> 25 ∘C), likely because GY waters are Fe-depleted (Moutin et al., 2008; Bonnet et al., 2008). When the high DIP, low DIN (dissolved inorganic N) waters from the gyre are advected west of the Tonga trench in Fe-rich and warm (> 25 ∘C) waters, all environmental conditions are fulfilled for diazotrophs to bloom extensively. According to Moutin et al. (2018), the strong depth difference between the nitracline and the phosphacline in MA waters associated with winter mixing allows a seasonal replenishment of DIP, which creates an excess of P relative to N and thus also favors N2 fixation in this region. Further investigations are required to better quantify Fe input from both islands and shallow volcanoes and associated hydrothermal activity along the Tonga volcanic arc for the upper mixed layer, study the fate of hydrothermal plumes in the water column at the local and regional scales, and investigate the potential impact of such hydrothermal inputs on diazotrophic communities at the scale of the whole WTSP.

N2 fixation rates were significantly negatively correlated with concentrations, consistent with the high energetic cost of N2 fixation compared to assimilation (Falkowski, 1983). They were also negatively correlated with depth and logically positively correlated with PAR and seawater temperature, two parameters which are depth dependent. Most N2 fixation took place in the surface mixed layer and rates were ∼ 15 nmol N L−1 d−1 in MA waters with local maxima at stations SD1, SD6 and LDB and local minima at SD8 and SD10. Trichodesmium, the most abundant diazotroph enumerated at those stations (Stenegren et al., 2018), is buoyant, and horizontal advection is well known to result in patchy distributions of Trichodesmium in the surface ocean (Dandonneau et al., 2003), with huge surface accumulations named slicks, as observed during OUTPACE (Stenegren et al., 2018), surrounded by areas with lower accumulations. These physical processes may explain the differences between stations rather than local enrichments of nutrients due to islands as those three stations where the highest rates were measured are not located close to islands. However, the huge surface bloom observed at LDB (Fig. 1) and extensively studied by de Verneil et al. (2017) was mainly sustained by N2 fixation (secondary fueling picoplankton and diatoms, Caffin et al., 2018a), rather than deep nutrient inputs (de Verneil et al., 2017). This bloom had been drifting eastwards for several months and initially originated from Fiji and Tonga archipelagoes (https://outpace.mio.univ-amu.fr/spip.php?article160, last access: February 2016), which may have provided sufficient Fe to alleviate limitation and trigger this exceptional diazotroph bloom.

4.3 Trichodesmium: the major contributor to N2 fixation in the WTSP

In MA waters, the dominant diazotroph phylotypes quantified using nifH quantitative PCR assays were Trichodesmium spp. and UCYN-B (Stenegren et al., 2018), which commonly peaked at > 106 nifH copies L−1 in surface (0–50 m) waters. DDAs (mainly het-1, but het-2 and het-3 were also detected) were the next most abundant diazotrophs (Stenegren et al., 2018). This result is consistent with the fact that abundances of those phylotypes co-varied and were significantly positively correlated with N2 fixation rates (Table 2). The two UCYN-A lineages (UCYN-A1 and UCYN-A2) were less abundant (< 1.0–1.5 % of total nifH copies, Stenegren et al., 2018) and not significantly correlated with N2 fixation rates (Table 2).

The relative contribution of different diazotroph phylotypes to bulk N2 fixation has been largely investigated through bulk and size fractionation measurements (usually comparing > and < 10 µm size fraction N2 fixation rates), which may be misleading since some small-size diazotrophs are attached to large-size particles (Benavides et al., 2016; Bonnet et al., 2009) or form colonies or symbioses with diatoms (e.g., UCYN-B, Foster et al., 2011, 2013) and some diazotrophic-derived N released by diazotrophs is assimilated by small and large non-diazotrophic plankton (e.g., Bonnet et al., 2016a). Here we directly measured the in situ cell-specific N2 fixation activity of the two dominating diazotroph groups in MA waters: Trichodesmium and UCYN-B.

At all three studied stations, Trichodesmium dominated, accounting for 68.0–91.8 % of the diazotroph community, followed by UCYN-B, accounting for 0.3–31.7 %. In addition, Trichodesmium and UCYN-B had the highest measured gene expression (102–105 cDNA nifH copies L−1). It was not surprising that UCYN-B had a high gene expression given that the sampling time occurred later in the day (17:00–21:00); however, both Trichodesmium and het-1 (which typically reduce N2 and express nifH highest during the day, Church et al., 2005) had a detectable and often equally as high expression as UCYN-B. Cell-specific N2 fixation rates reported here are on the same order of magnitude as those reported for field populations of Trichodesmium (Berthelot et al., 2016; Stenegren et al., 2018) and UCYN-B (Foster et al., 2013). Trichodesmium was always the major contributor to N2 fixation, accounting for 47.1–83.8 % of bulk N2 fixation, while UCYN-B never exceeded 6.1–10.1 %, despite accounting for > 30 % of the diazotroph community at SD6. This may be linked with the lower 15N enrichment at SD6 (0.517 ± 0.237 at. %), which is due to a high proportion of inactive cells (at. % close to natural abundance) compared to SD2, where the majority of cells were active and highly 15N-enriched (1.163 ± 0.531 at. %). Such heterogeneity in N2 fixation rates among UCYN-B-like cells has already been reported by Foster et al. (2013). Overall, these results show that the most abundant phylotype (Trichodesmium) accounts for the majority of N2 fixation, but not in the same proportion, further indicating that the abundance of micro-organisms in seawater cannot be equated to activity, which has already been reported for other functional groups such as bacteria (Boutrif et al., 2011). In the North Pacific Gyre (station ALOHA), Foster et al. (2013) report a higher contribution of UCYN-B to daily bulk N2 fixation (24–63 %) during the summer season, indicating that this group likely contributes more to the N budget at station ALOHA than in the WTSP, where Trichodesmium seems to be the major player.

N2 fixation was significantly positively correlated with Chl a, PON, POC and BSi concentrations, as well as with primary production, suggesting a tight coupling between N2 fixation, primary production and biomass accumulation in the water column. Based on our measured C : N ratios at each depth, the computation of the N demand derived from primary production measured during OUTPACE (Johnson et al., 2007) indicates that N2 fixation fueled on average 8.2 ± 1.9 % (range 5.9 to 11.5 %) of total primary production in the WTSP. This contribution is higher than in other oligotrophic regions such as the northwestern Pacific (Shiozaki et al., 2013), ETSP (Raimbault and Garcia, 2008), northeastern Atlantic (Benavides et al., 2013), or the Mediterranean Sea (Bonnet et al., 2011; Ridame et al., 2014), where it is generally < 5 %. However, it is comparable to results found further north in the Solomon Sea (N2 fixation fueled 9.4 % of primary production, Berthelot et al., 2017), which is part of the WTSP “hotspot” for N2 fixation (Bonnet et al., 2017). Caffin et al. (2018b, a) show that N2 fixation represents the major source (> 90 %) of new N to the upper photic (productive) layer during the OUTPACE cruise, before atmospheric inputs and nitrate diffusion across the thermocline, indicating that N2 fixation supported nearly all new production in this region during austral summer conditions.

The large amount of N provided by N2 fixation likely stimulated the growth of non-diazotrophic plankton as suggested by significant positive correlations between N2 fixation rates and the abundance of Prochlorococcus spp., Synechococcus spp., heterotrophic bacteria and protists. 15N2-based transfer experiments coupled with nanoSIMS experiments designed to trace the transfer of 15N in the planktonic food web demonstrated that ∼ 10 % of diazotroph-derived N is rapidly (24–48 h) transferred to non-diazotrophic phytoplankton (mainly diatoms and bacteria) in coastal waters of the WTSP (Bonnet et al., 2016a, b; Berthelot et al., 2016). The same experiments performed in offshore waters during the present cruise confirm that ∼ 10 % of recently fixed N2 is also transferred to picophytoplankton and bacteria after 48 h (Caffin et al., 2018a). This is in accordance with Van Wambeke et al. (2018), who report that N2 fixation fuels 40 to 70 % of the bacteria N demand in MA waters. This further demonstrates that N2 fixation acts as an efficient natural N fertilization in the WTSP, potentially fueling subsequent export of organic material below the photic layer. Caffin et al. (2018a, b) estimated that the e-ratio, which quantifies the efficiency of a system in exporting particulate carbon relative to primary production (e-ratio = POC export∕PP), was 3 times higher (p < 0.05) in MA waters compared to GY waters. Moreover, e-ratio values were as high as 9.7 % in MA waters, i.e., higher than the e-ratios in most studied oligotrophic regions (Karl et al., 2012; Raimbault and Garcia, 2008), where they rarely exceed 1 %, indicating that production sustained by N2 fixation is efficiently exported in the WTSP. Diazotrophs were recovered in sediment traps during the cruise (Caffin et al., 2018a, b), but their biomass only accounted for ∼ 5 % (locally 30 % at LDA) of the N biomass in the traps, indicating that most of the export was indirect, i.e., after transfer of diazotroph-derived N to the surrounding planktonic communities that were subsequently exported. A δ15N budget performed during the OUTPACE cruise reveals that N2 fixation supports exceptionally high (> 50 % and locally > 80 % of) export production in MA waters (Knapp et al., 2018). Together these results suggest that N2 fixation plays a critical role in export in this globally important region for elevated N2 fixation.

The magnitude and geographic distribution of N2 fixation control the rate of primary productivity and vertical export of carbon in the oligotrophic ocean; thus, accurate estimates of N2 fixation are of primary importance for oceanographers to constrain and predict the evolution of marine biogeochemical carbon and N cycles. The number of N2 fixation estimates have increased dramatically at the global scale over the past 3 decades (Luo et al., 2012). The results reported here show that some poorly sampled areas such as the WTSP provide unique conditions for diazotrophs to fix at high rates and contribute to the need to update current N2 fixation estimates for the Pacific Ocean. Further studies would be required to assess the seasonal variability of N2 fixation in this region and perform accurate N budgets. Nonetheless, such high N2 fixation rates question whether or not these high N inputs can balance the N losses in the ETSP. A recent study based on the N∗ (the excess of N relative to P) at the whole South Pacific scale Fumenia et al. (2018) reveals a strong positive N∗ anomaly (indicative of N2 fixation) in the surface and thermocline waters of the WTSP, which potentially influences the geochemical signature of the thermocline waters further east in the South Pacific through the regional circulation. However, the WTSP is chronically undersampled, and a better description of the mesoscale and general circulation would be necessary to assess how N sources and sinks are coupled at the South Pacific scale.

All data and metadata are available at the following web address: http://www.obs-vlfr.fr/proof/php/outpace/outpace.php, last access: June 2018.

SB designed the experiments; SB, MC, HB and MB carried them out at sea. MC, HB, RAF, SHN, CG and OG analyzed the samples; MC and SB analyzed the data. SB prepared the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article is part of the special issue “Interactions between planktonic organisms and biogeochemical cycles across trophic and N2 fixation gradients in the western tropical South Pacific Ocean: a multidisciplinary approach (OUTPACE experiment)”. It is not associated with a conference.

This research is a contribution of the OUTPACE (Oligotrophy from

Ultra-oligoTrophy PACific Experiment) project

(https://outpace.mio.univ-amu.fr/, last access: June 2018) funded by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (grant

ANR-14-CE01-0007-01), the LEFE-CyBER program (CNRS-INSU), the Institut de

Recherche pour le Développement (IRD), the GOPS program (IRD) and the CNES

(BC T23, ZBC 4500048836). The OUTPACE cruise

(http://dx.doi.org/10.17600/15000900, last access: June 2018) was managed by the MIO (OSU Institut Pytheas, AMU) from

Marseilles (France). The authors thank the crew of the R/V

L'Atalante for outstanding shipboard operations. Gilles Rougier and

Marc Picheral are warmly thanked for their efficient help in CTD rosette

management and data processing, as well as Catherine Schmechtig for the

LEFE-CyBER database management and Thibaut Wagener for providing the map of

bathymetry. Aurelia Lozingot is acknowledged for the administrative work. Mar Benavides was funded by the People Programme

(Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions) of the European Union's Seventh Framework

Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under REA grant agreement number 625185. The

participation, nucleic acid sampling and analysis were provided to Rachel A.

Foster by the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. Rachel A. Foster also

acknowledges the assistance by Lotta Berntzon, Marcus Stenegren and Andrea

Caputo. The satellite products are provided by CLS with the support of

CNES.

Edited by: Douglas G. Capone

Reviewed by: Carolin Löscher and three anonymous referees

Aminot, A. and Kérouel, R.: Dosage automatique des nutriments dans les eaux marines: méthodes en flux continu, Editions Quae, 2007. a

Benavides, M. and Voss, M.: Five decades of N2 fixation research in the North Atlantic Ocean, Frontiers in Marine Science, 2, 1–20, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2015.00040, 2015. a

Benavides, M., Bronk, D. A., Agawin, N. S., Pérez-Hernández, M. D., Hernández-Guerra, A., and Arístegui, J.: Longitudinal variability of size-fractionated N2 fixation and DON release rates along 24.5∘ N in the subtropical North Atlantic, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 118, 3406–3415, 2013. a

Benavides, M., Moisander, P. H., Berthelot, H., Dittmar, T., and Grosso, O.: Mesopelagic N2 fixation related to organic matter composition in the Solomon and Bismarck Seas (Southwest Pacific), PLoS One, 10, 12, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0143775, 2015. a

Benavides, M., Moisander, P. H., Daley, M. C., Bode, A., and Arístegui, J.: Longitudinal variability of diazotroph abundances in the subtropical North Atlantic Ocean, J. Plankton Res., 38, 662–672, 2016. a

Benavides, M., Berthelot, H., Duhamel, S., Raimbault, P., and Bonnet, S.: Dissolved organic matter uptake by Trichodesmium in the Southwest Pacific, Sci. Rep.-UK, 7, 41315, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep41315, 2017. a

Berthelot, H., Bonnet, S., Grosso, O., Cornet, V., and Barani, A.: Transfer of diazotroph-derived nitrogen towards non-diazotrophic planktonic communities: a comparative study between Trichodesmium erythraeum, Crocosphaera watsonii and Cyanothece sp., Biogeosciences, 13, 4005–4021, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-13-4005-2016, 2016. a, b, c, d

Berthelot, H., Benavides, M., Moisander, P. H., Grosso, O., and Bonnet, S.: High-nitrogen fixation rates in the particulate and dissolved pools in the Western Tropical Pacific (Solomon and Bismarck Seas), Geophys. Res. Lett., 2, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL073856, 2017. a, b, c, d

Blain, S., Bonnet, S., and Guieu, C.: Dissolved iron distribution in the tropical and sub tropical South Eastern Pacific, Biogeosciences, 5, 269–280, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-5-269-2008, 2008. a

Bock, N., Van Wambeke, F., Dion, M., and Duhamel, S.: Microbial community structure in the Western Tropical South Pacific, Biogeosciences Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-2017-562, in review, 2018. a

Bonnet, S. and Guieu, C.: Atmospheric forcing on the annual iron cycle in the Mediterranean Sea. A one-year survey, J. Geophys. Res., 111, C9, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JC003213, 2006. a

Bonnet, S., Guieu, C., Bruyant, F., Prášil, O., Van Wambeke, F., Raimbault, P., Moutin, T., Grob, C., Gorbunov, M. Y., Zehr, J. P., Masquelier, S. M., Garczarek, L., and Claustre, H.: Nutrient limitation of primary productivity in the Southeast Pacific (BIOSOPE cruise), Biogeosciences, 5, 215–225, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-5-215-2008, 2008. a, b

Bonnet, S., Biegala, I. C., Dutrieux, P., Slemons, L. O., and Capone, D. G.: Nitrogen fixation in the western equatorial Pacific: Rates, diazotrophic cyanobacterial size class distribution, and biogeochemical significance, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 23, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008gb003439, 2009. a, b, c

Bonnet, S., Grosso, O., and Moutin, T.: Planktonic dinitrogen fixation along a longitudinal gradient across the Mediterranean Sea during the stratified period (BOUM cruise), Biogeosciences, 8, 2257–2267, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-8-2257-2011, 2011. a, b

Bonnet, S., Rodier, M., Turk-Kubo, K., Germineaud, C., Menkes, C., Ganachaud, A., Cravatte, S., Raimbault, P., Campbell, E., Quéroué, F., Sarthou, G., Desnues, A., Maes, C., and Eldin, G.: Contrasted geographical distribution of N2 fixation rates and nifH phylotypes in the Coral and Solomon Seas (South-Western Pacific) during austral winter conditions, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 29, 11, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GB005117, 2015. a, b, c, d

Bonnet, S., Berthelot, H., Turk-Kubo, K. A., Cornet-Barthaux, V., Fawcett, S., Berman-Frank, I., Barani, A., Grégori, G., Dekaezemacker, J., Benavides, M., and Capone, D. G.: Diazotroph derived nitrogen supports diatom growth in the South West Pacific: A quantitative study using nanoSIMS, Limnol. Oceanogr., 61, 1549–1562, https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.10300, 2016a. a, b, c, d, e, f

Bonnet, S., Berthelot, H., Turk-Kubo, K., Fawcett, S., Rahav, E., L'Helguen, S., and Berman-Frank, I.: Dynamics of N2 fixation and fate of diazotroph-derived nitrogen in a low-nutrient, low-chlorophyll ecosystem: results from the VAHINE mesocosm experiment (New Caledonia), Biogeosciences, 13, 2653–2673, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-13-2653-2016, 2016b. a, b, c

Bonnet, S., Caffin, M., Berthelot, H., and Moutin, T.: Hot spot of N2 fixation in the western tropical South Pacific pleads for a spatial decoupling between N2 fixation and denitrification, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 114, E2800–E2801, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1619514114, 2017. a, b, c, d

Böttjer, D., Dore, J. E., Karl, D. M., Letelier, R. M., Mahaffey, C., Wilson, S. T., Zehr, J. P., and Church, M. J.: Temporal variability of nitrogen fixation and particulate nitrogen export at Station ALOHA, Limnol. Oceanogr., 62, 200–216, https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.10386, 2017. a

Breitbarth, E., Oschlies, A., and LaRoche, J.: Physiological constraints on the global distribution of Trichodesmium – effect of temperature on diazotrophy, Biogeosciences, 4, 53–61, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-4-53-2007, 2007. a

Boutrif, M., Garel, M., Cottrell, M. T., and Tamburini, C.: Assimilation of marine extracellular polymeric substances by deep-sea prokaryotes in the NW Mediterranean Sea, Environmental microbiology reports, 3, 705–709, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-2229.2011.00285.x, 2011.

Caffin, M., Berthelot, H., Cornet-Barthaux, V., Barani, A., and Bonnet, S.: Transfer of diazotroph-derived nitrogen to the planktonic food web across gradients of N2 fixation activity and diversity in the western tropical South Pacific Ocean, Biogeosciences, 15, 3795–3810, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-15-3795-2018, 2018a. a, b

Caffin, M., Moutin, T., Foster, R. A., Bouruet-Aubertot, P., Doglioli, A. M., Berthelot, H., Guieu, C., Grosso, O., Helias-Nunige, S., Leblond, N., Gimenez, A., Petrenko, A. A., de Verneil, A., and Bonnet, S.: N2 fixation as a dominant new N source in the western tropical South Pacific Ocean (OUTPACE cruise), Biogeosciences, 15, 2565–2585, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-15-2565-2018, 2018b. a, b, c, d

Carpenter, E. J., Subramaniam, A., and Capone, D. G.: Biomass and primary productivity of the cyanobacterium Trichodesmium spp. in the tropical N Atlantic ocean, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. I, 51, 173–203, 2004. a

Church, M. J., Short, C. M., Jenkins, B. D., Karl, D. M., and Zehr, J. P.: Temporal patterns of nitrogenase gene (nifH) expression in the oligotrophic North Pacific Ocean, Appl. Environ. Microb., 71, 5362–5370, https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.71.9.5362-5370.2005, 2005. a

Cook, J.: The Voyages of Captain James Cook, vol. 2, William Smith, 1842. a

Dabundo, R., Lehmann, M. F., Treibergs, L., Tobias, C. R., Altabet, M. A., Moisander, A. M., and Granger, J.: The contamination of commercial 15N2 gas stocks with 15N labeled nitrate and ammonium and consequences for nitrogen fixation measurements, PLoS One, 9, e110335, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110335, 2014. a

Dandonneau, Y., Vega, A., Loisel, H., du Penhoat, Y., and Menkes, C.: Oceanic Rossby waves acting as a “hay rake” for ecosystem floating by-products, Science, 302, 1548–1551, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1090729, 2003. a

de Boyer Montégut, C., Madec, G., Fischer, A. S., Lazar, A., and Iudicone, D.: Mixed layer depth over the global ocean: An examination of profile data and a profile-based climatology, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 109, C12, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004JC002378, 2004. a

Dekaezemacker, J. and Bonnet, S.: Sensitivity of N2 fixation to combined nitrogen forms ( and ) in two strains of the marine diazotroph Crocosphaera watsonii (Cyanobacteria), Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., 438, 33–46, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps09297, 2011. a

Dekaezemacker, J., Bonnet, S., Grosso, O., Moutin, T., Bressac, M., and Capone, D. G.: Evidence of active dinitrogen fixation in surface waters of the Eastern Tropical South Pacific during El Nino and La Nina events and evaluation of its potential nutrient controls, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 27, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1002/gbc.20063, 2013. a, b

Deutsch, C. A., Sarmiento, J. L., Sigman, D. M., Gruber, N., and Dunne, J. P.: Spatial coupling of nitrogen inputs and losses in the ocean, Nature, 445, 163–167, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05392, 2007. a

de Verneil, A., Rousselet, L., Doglioli, A. M., Petrenko, A. A., and Moutin, T.: The fate of a southwest Pacific bloom: gauging the impact of submesoscale vs. mesoscale circulation on biological gradients in the subtropics, Biogeosciences, 14, 3471–3486, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-14-3471-2017, 2017. a, b

Dugdale, R. C. and Goering, J. J.: Uptake of new and regenerated forms of nitrogen in primary productivity, Limnol. Oceanogr., 12, 196–206, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1967.12.2.0196, 1967. a

Dupouy, C., Neveux, J., Subramaniam, A., Mulholland, M. R., Montoya, J. P., Campbell, L., Carpenter, E. J., and Capone, D. G.: Satellite captures Trichodesmium blooms in the southwestern tropical Pacific, EOS Transactions American Geophysical Union, 81, 13–16, 2000. a

Dupouy, C., Benielli-Gary, D., Neveux, J., Dandonneau, Y., and Westberry, T. K.: An algorithm for detecting Trichodesmium surface blooms in the South Western Tropical Pacific, Biogeosciences, 8, 3631–3647, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-8-3631-2011, 2011. a

Dutheil, C., Aumont, O., Gorguès, T., Lorrain, A., Bonnet, S., Rodier, M., Dupouy, C., Shiozaki, T., and Menkes, C.: Modelling the processes driving Trichodesmium sp. spatial distribution and biogeochemical impact in the tropical Pacific Ocean, Biogeosciences Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-2017-559, in review, 2018.

Eppley, R. W. and Peterson, B. J.: Particulate organic matter flux and planktonic new production in the deep ocean, Nature, 282, 677–680, https://doi.org/10.1038/282677a0, 1979. a

Falkowski, P. G.: Light-shade adaptation and vertical mixing of marine phytoplankton: a comparative field study, J. Mar. Res., 41, 215–237, 1983.

Fernández, C., Farías, L., and Ulloa, O.: Nitrogen Fixation in Denitrified Marine Waters, PLoS One, 6, e20539, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020539, 2011. a

Fernández, C., González, M. L., Muñoz, C., Molina, V., and Farias, L.: Temporal and spatial variability of biological nitrogen fixation off the upwelling system of central Chile (35–38.5∘ S), J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 120, 3330–3349, 2015. a

Fitzsimmons, J. N., Boyle, E. A., and Jenkins, W. J.: Distal transport of dissolved hydrothermal iron in the deep South Pacific Ocean, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 111, 16654–16661, 2014. a

Foster, R. A., Goebel, N. L., and Zehr, J. P.: Isolation of Calothrix rhizosoleniae (cyanobacteria) strain SC01 from Chaetoceros (Bacillariophyta) spp. diatoms of the Subtropical North Pacific Ocean, J. Phycol., 45, 1028–1037, 2010. a, b

Foster, R. A., Kuypers, M. M. M., Vagner, T., Paerl, R. W., Musat, N., and Zehr, J. P.: Nitrogen fixation and transfer in open ocean diatom-cyanobacterial symbioses, ISME J., 5, 1484–1493, 2011. a, b

Foster, R. A., Sztejrenszus, S., and Kuypers, M. M. M.: Measuring carbon and N2 fixation in field populations of colonial and free living cyanobacteria using nanometer scale secondary ion mass spectrometry, J. Phycol., 49, 502–516, 2013. a, b, c, d

Fumenia, A., Moutin, T., Bonnet, S., Benavides, M., Petrenko, A., Helias Nunige, S., and Maes, C.: Excess nitrogen as a marker of intense dinitrogen fixation in the Western Tropical South Pacific Ocean: impact on the thermocline waters of the South Pacific, Biogeosciences Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-2017-557, in review, 2018. a, b

Gradoville, M. R., Bombar, D., Crump, B. C., Letelier, R. M., Zehr, J. P., and White, A. E.: Diversity and activity of nitrogen-fixing communities across ocean basins, Limnol. Oceanogr., 62, 1895–1909, 2017. a

Gruber, N.: The marine nitrogen cycle: Overview and challenges. Nitrogen in the Marine Environment, edited by: Capone, D. G., Bronk, D. A., Mulholland, M. R., and Carpenter, E. J., Academic, San Diego, 1–50, 2008. a

Gruber, N.: Elusive marine nitrogen fixation, P. Natl. Acade. Sci. USA, 113, 4246–4248, 2016. a, b

Guieu, C., Bonnet, S., Petrenko, A., Menkes, C., Chavagnac, V., Desboeufs, C., Maes, C., and Moutin, T.: Iron from a submarine source impacts the productive layer of the Western Tropical South Pacific (WTSP), Sci. Rep.-UK, 8, 9075, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-27407-z, 2018. a, b, c, d, e

Johnson, K. S., Elrod, V., Fitzwater, S., Plant, J., Boyle, E., Bergquist, B., Bruland, K., Aguilar-Islas, A., Buck, K., Lohan, M., Smith, G. J., Sohst, B., Coale, K., Gordon, M., Tanner, S., Measures, C., Moffett, J., Barbeau, K., King, A., Bowie, A., Chase, Z., Cullen, J., Laan, P., Landing, W., Mendez, J., Milne, A., Obata, H., Doi, T., Ossiander, L., Sarthou, G., Sedwick, P., Van den Berg, S., Laglera-Baquer, L., Wu, J.-F., and Cai, Y.: Developing standards for dissolved iron in seawater, Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union, 88, 131–132, 2007. a, b

Kana, T. M., Darkangelo, C., Hunt, M. D., Oldham, J. B., Bennett, G. E., and Cornwell, J. C.: A membrane inlet mass spectrometer for rapid high precision determination of N2, O2, and Ar in environmental water samples, Anal. Chem., 66, 4166–4170, 1994. a

Karl, D. M., Bates, N. R., Emerson, S., Harrison, P. J., del Octavio Llinâs, C. J., Liu, K.-K., Marty, J.-C., Michaels, A. F., Miquel, J. C., Neuer, S., Nojiri, Y., and Wong, C. S.: Temporal studies of biogeochemical processes determined from ocean time-series observations during the JGOFS era, in: Ocean Biogeochemistry, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 239–267, 2003. a

Karl, D. M., Church, M. J., Dore, J. E., Letelier, R. M., and Mahaffey, C.: Predictable and efficient carbon sequestration in the North Pacific Ocean supported by symbiotic nitrogen fixation, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 109, 1842–1849, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1120312109, 2012. a, b, c

Klawonn, I., Lavik, G., Böning, P., Marchant, H., Dekaezemacker, J., Mohr, W., and Ploug, H.: Simple approach for the preparation of 15-15N2-enriched water for nitrogen fixation assessments: evaluation, application and recommendations, Front. Microbiol., 6, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.00769, 2015. a, b

Knap, A. H., Michaels, A., Close, H., Ducklow, H. W., and Dickson, A. G. (Eds.): Protocols for the Joint Global Ocean Flux Study (JGOFS) core measurements, JGOFS Rep. 19, 170 p., Carbon Dioxide Inf. Anal. Cent., Oak Ridge Natl. Lab., Oak Ridge, Tenn., 1994. a

Knapp, A. N., Dekaezemacker, J., Bonnet, S., Sohm, J. A., and Capone, D. G.: Sensitivity of Trichodesmium erythraeum and Crocosphaera watsonii abundance and N2 fixation rates to varying and concentrations in batch cultures, Aquat. Microb. Ecol., 66, 223–236, 2012. a

Knapp, A. N., Casciotti, K. L., Berelson, W. M., Prokopenko, M. G., and Capone, D. G.: Low rates of nitrogen fixation in eastern tropical South Pacific surface waters, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 113, 4398–4403, 2016. a

Knapp, A. N., McCabe, K. M., Grosso, O., Leblond, N., Moutin, T., and Bonnet, S.: Distribution and rates of nitrogen fixation in the western tropical South Pacific Ocean constrained by nitrogen isotope budgets, Biogeosciences, 15, 2619–2628, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-15-2619-2018, 2018. a

Labatut, M., Lacan, F., Pradoux, C., Chmeleff, J., Radic, A., Murray, J. W., Poitrasson, F., Johansen, A. M., and Thil, F.: Iron sources and dissolved-particulate interactions in the seawater of the Western Equatorial Pacific, iron isotope perspectives, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 28, 1044–1065, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GB004928, 2014. a

Loescher, C. R., Großkopf, T., Desai, F. D., Gill, D., Schunck, H., Croot, P. L., and Kuypers, M. M.: Facets of diazotrophy in the oxygen minimum zone waters off Peru, The ISME journal, 8, 2180, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.71, 2014. a

Luo, Y.-W., Doney, S. C., Anderson, L. A., Benavides, M., Berman-Frank, I., Bode, A., Bonnet, S., Boström, K. H., Böttjer, D., Capone, D. G., Carpenter, E. J., Chen, Y. L., Church, M. J., Dore, J. E., Falcón, L. I., Fernández, A., Foster, R. A., Furuya, K., Gómez, F., Gundersen, K., Hynes, A. M., Karl, D. M., Kitajima, S., Langlois, R. J., LaRoche, J., Letelier, R. M., Marañón, E., McGillicuddy Jr., D. J., Moisander, P. H., Moore, C. M., Mouriño-Carballido, B., Mulholland, M. R., Needoba, J. A., Orcutt, K. M., Poulton, A. J., Rahav, E., Raimbault, P., Rees, A. P., Riemann, L., Shiozaki, T., Subramaniam, A., Tyrrell, T., Turk-Kubo, K. A., Varela, M., Villareal, T. A., Webb, E. A., White, A. E., Wu, J., and Zehr, J. P.: Database of diazotrophs in global ocean: abundance, biomass and nitrogen fixation rates, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 4, 47–73, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-4-47-2012, 2012. a, b, c, d, e

Luo, Y.-W., Lima, I. D., Karl, D. M., Deutsch, C. A., and Doney, S. C.: Data-based assessment of environmental controls on global marine nitrogen fixation, Biogeosciences, 11, 691–708, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-11-691-2014, 2014. a

Massoth, G., Baker, E., Worthington, T., Lupton, J., de Ronde, C., Arculus, R., Walker, S., Nakamura, K. I., Ishibashi, J. I., and Stoffers, P.: Multiple hydrothermal sources along the south Tonga arc and Valu Fa Ridge, Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst., 8, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GC001675, 2007. a

Messer, L. F., Mahaffey, C., M Robinson, C., Jeffries, T. C., Baker, K. G., Bibiloni Isaksson, J., Ostrowski, M., Doblin, M. A., Brown, M. V., and Seymour, J. R.: High levels of heterogeneity in diazotroph diversity and activity within a putative hotspot for marine nitrogen fixation, ISME J., 10, 1499, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2015.205, 2015. a, b

Mohr, W., Großkopf, T., Wallace, D. W. R., and LaRoche, J.: Methodological underestimation of oceanic nitrogen fixation rates, PLoS ONE, 5, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0012583, 2010. a

Moisander, P. H., Beinart, R. A., Hewson, I., White, A. E., Johnson, K. S., Carlson, C. A., Montoya, J. P., and Zehr, J. P.: Unicellular Cyanobacterial Distributions Broaden the Oceanic N2 Fixation Domain, Science, 327, 1512–1514, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1185468, 2010. a, b

Moisander, P. H., Zhang, R. F., Boyle, E. A., Hewson, I., Montoya, J. P., and Zehr, J. P.: Analogous nutrient limitations in unicellular diazotrophs and Prochlorococcus in the South Pacific Ocean, ISME J., 6, 733–744, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.152, 2011. a

Montoya, J. P., Voss, M., Kahler, P., and Capone, D. G.: A simple, high-precision, high-sensitivity tracer assay for N2 fixation, Appl. Environ. Microb., 62, 986–993, 1996. a, b

Montoya, J. P., Holl, C. M., Zehr, J. P., Hansen, A., Villareal, T. A., and Capone, D. G.: High rates of N2 fixation by unicellular diazotrophs in the oligotrophic Pacific Ocean, Nature, 430, 1027–1031, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02824, 2004. a, b

Moore, C. M., Mills, M. M., Arrigo, K. R., Berman-Frank, I., Bopp, L., Boyd, P. W., Galbraith, E. D., Geider, R. J., Guieu, C., Jaccard, S. L., Jickells, T. D., La Roche, J., Lenton, T. M., Mahowald, N. M., Marañón, E., Marinov, I., Moore, J. K., Nakatsuka, T., Oschlies, A., Saito, M. A., Thingstad, T. F., Tsuda, A., and Ulloa, O.: Processes and patterns of oceanic nutrient limitation, Nat. Geosci., 6, 701–710, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1765, 2013. a

Moutin, T., Van Den Broeck, N., Beker, B., Dupouy, C., Rimmelin, P., and Le Bouteiller, A.: Phosphate availability controls Trichodesmium spp. biomass in the SW Pacific Ocean, Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., 297, 15–21, https://doi.org/10.3354/meps297015, 2005. a

Moutin, T., Karl, D. M., Duhamel, S., Rimmelin, P., Raimbault, P., Van Mooy, B. A. S., and Claustre, H.: Phosphate availability and the ultimate control of new nitrogen input by nitrogen fixation in the tropical Pacific Ocean, Biogeosciences, 5, 95–109, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-5-95-2008, 2008. a, b, c, d